Back to Jeremy Schiff's personal homepage

Back to Jeremy Schiff's Hodja homepage

Back to "Once the Hodja" mainpage

OH, ALLAH! I need money! I need one thousand ghurush!" The wheedling voice of Nasr-ed-Din Hodja rose from behind his courtyard walls, built high of sun-dried brick of clay and straw. Whether or not the prayer rose to the ears of Allah, it was loud enough for the ears of the neighbors.

Siraj-ed-Din Bey, the wealthy merchant whose yard adjoined the Hodja's, looked from his upstairs window. He could see Nasr-ed-Din Hodja kneeling on a well-worn prayer rug, sitting erect, then bowing repeatedly till his forehead touched the ground, as he murmured his prayer again and again.

"Oh, Allah! I need money - much money I need one thousand ghurush. Eight hund ghurush would not be enough, nor nine hundred, nor nine hundred and ninety-nine. I must have exactly one thousand ghurusH. A smaller sum I could not possibly accept. Oh, Allah, send me one thousand ghurush - may it come soon."

Siraj-ed-Din Bey, listening in his open window, smiled as he would have smiled at a child praying for a large piece of rahat lokum. He smiled at the Hodja's queer idea of prayer. Siraj-ed-Din Bey knew that if a man really wanted something, he had to mix work with his prayers.

The voice chanted on, "One thousand ghurush, Allah! Not one coin less than a thousand!"

"It is time to teach that simple old Hodja not to pray without helping Allah to make his prayers come true," thought Siraj-ed-Din Bey, who was really fond of his kindly neighbor. He laughed as a scheme grew in his mind.

Turning noiselessly from his high window, Siraj-ed-Din Bey hurried to the room where his money was hidden. Carefully he counted out nine hundred and ninety-nine ghurush. He recounted it to be sure there was not a single coin more or less. He put the money in a bag, tied it securely, and tiptoed back to the open window. His stockinged feet on his thick rugs made not a sound. Taking careful aim, he tossed the money bag. It barely missed the Hodja's bowed head and landed with a merry chinking on the cobblestones. Then Siraj-ed-Din Bey hurried to his wife's room, where he could watch unseen from behind her latticed window.

Without waiting to thank Allah, Nasr-ed-Din Hodja began counting the money. He counted it again and again. He tried to divide it into ten piles of one hundred ghurush each, but, no matter how many times he counted, one pile had but ninety-nine coins.

Siraj-ed-Din Bey and his wife, peering unseen through the latticed window, clapped their hands tightly over their mouths to hold back the laughter.

"I will let him count once more," whispered Siraj-ed-Din Bey to his wife. "Then I will explain the joke to him. He will laugh as hard as we.

But Siraj-ed-Din Bey had waited too long. Nasr-ed-Din Hodja did not count the coins again. Instead, he put them all snugly to rest in the money bag, tied the bag securely, and tucked it out of sight in his wide girdle. Then he knelt on the prayer rug.

"Oh, Allah!" prayed the Hodja. "You did not count the ghurush correctly. There were not quite one thousand. You owe me one more ghurush. Send me that whenever it is convenient. And thanks, many thanks, for the nine hundred and ninety-nine you did send me."

If it had not been for the lattice, Siraj-ed-Din Bey would have leaped through his window without bothering about stairs or gates. Passers-by gaped to see the wealthiest merchant of Ak Shehir rush from his door as though pursued by jackals and bang on Hodja's street gate. When the street door was pulled open for him, Siraj-ed-Din Bey shot through it toward the Hodja.

"Give me back my money bag!" shouted Siraj-ed-Din Bey, too excited to care who heard. He did not notice the open-mouthed crowd at the Hodja's gate. "Give me back my nine hundred and ninety-nine ghurush!"

"Your money bag? Your nine hundred and ninety-nine ghurush?"

"Yes, mine! I tossed them over the wall just for a joke. You said you would not accept less than a thousand ghurush. I was just trying to show you how silly such a prayer must sound to Allah."

"You tossed it? No, indeed! The money bag was a gift from Allah. It fell directly from heaven in answer to my prayer."

"I will take you and the money bag to court," said Siraj-ed-Din Bey, laying an angry hand on Nasr-ed-Din Hodja's shoulder. "We'll soon see whether it fell from heaven or from my window!"

"Yes, we'll have it decided in court." The Hodja always relished the court, with its chances for talk and excitement. "You will soon learn that this money fell from heaven."

"Well, hurry! Haidi bakalim!" Siraj-ed Din Bey took a step toward the gate, but the Hodja hesitated.

"My coat! Fatima is mending it. I cannot go to court without it." The Hodja looked down at his shabby clothes.

"I will lend you a coat."

"But my donkey! She has a lame foot. I cannot ride her a long distance and, of course, we are in too much of a hurry to walk."

"I will lend you a horse."

"But a saddle and bridle! My little donkey's would never fit your big horse."

"I will lend you a saddle and bridle. Come into my yard and I will fit you out for the trip to court."

Nasr-ed-Din Hodja rolled up his prayer rug and put it away. He waved good-bye toward his wife's latticed window. He could not see her, but he knew her well enough to be sure she was not missing a word or a gesture. Then he followed Siraj-ed-Din Bey.

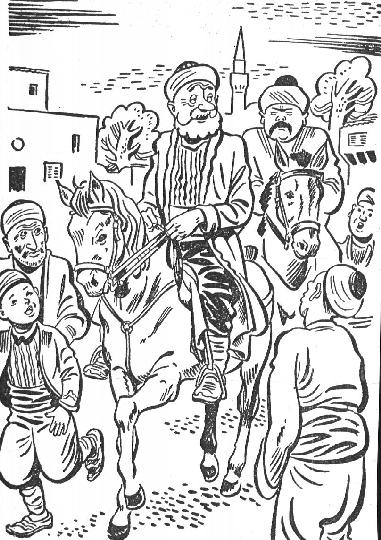

In a short time the two men left the merchant's house on horseback. The merchant had supplied Nasr-ed-Din Hodja with a spirited dappled gray, which he rode as though it were a donkey. The Hodja bowed to left and to right as he went bouncing through the streets in his borrowed grandeur. He felt very high and mighty, but the men in the streets knew it would take more than an expensive coat, an embroidered saddle, a jingling bridle, and a fine horse to make a dashing horseman of the Hodja.

Arriving at the court, Siraj-ed-Din Bey lost no time in telling his story to the Judge. As he talked, he was disturbed at the strange way the Hodja was watching him, smiling sadly and shaking his head slowly.

"Well, Nasr-ed-Din Hodja," said the Judge, "have you anything to say?"

"Poor Siraj-ed-Din Bey," sighed the Hodja, his voice fairly dripping sympathy. "How sad! How very, very sad! He was such a good neighbor and so highly respected by all! To think that he should have lost his mind!"

"Lost his mind?" snapped the Judge. "What do you mean?"

"Oh, didn't you know?" The Hodja went close to the Judge and whispered in a voice that could be heard throughout the room, "He thinks everything belongs to him. You heard his story about my money bag. Just try him on something else and he will be sure to say it is his. Ask him whose coat this is I have on my back."

"My coat, of course, exclaimed the merchant, not waiting for the Judge to ask. "The Hodja knows it is my coat."

The Hodja shook his head sadly. "Try something else, Judge. Ask him, for instance, whose saddle is on my dappled gray horse."

"My saddle, of course, and it's my bridle too," cried Siraj-ed-Din Bey. "The Hodja knows they are both mine."

"You see how pathetic it is," said the Hodja with a deep sigh of pity. "Poor man! He is so crazy that he might even claim my fine dappled gray horse."

"Of course I claim the horse," shouted the merchant. "I have owned that dappled gray since it was a colt."

The Hodja shrugged his shoulders. The Judge had evidence enough; let him decide.

"This is a strange case - a sad case," said the Judge thoughtfully. It was not easy to condemn the richest man in all Ak Shehir. "I believed Siraj-ed-Din Bey about tossing the money bag, though it was a rather wild story. Now I see differently. When he claims to own the Hodja's very coat and horse, saddle and bridle, he shows his mind is unbalanced. Siraj-ed-Din Bey, I suggest that you go home and take a good long rest. You have been working too hard, I am sure. Nasr-ed-Din Hodja, you may keep your money bag and all of your possessions that your unfortunate neighbor is trying to claim."

The two men rode in silence through the streets of Ak Shehir. Siraj-ed-Din Bey's shoulders sagged as though he had suddenly become an old man. Nasr-ed-Din Hodja bounced and gyrated with every step of the proud horse who was so unlike his donkey.

The merchant rode in at his own gate and turned to close it after himself. To his surprise, he was not alone. He was followed by the warmly grinning Hodja.

"Here is your money bag," said the Hodja, handing the heavy bag to the surprised merchant. "And your coat. And your horse with his saddle and bridle."

Siraj-ed-Din Bey, holding the money bag in one hand and the bridle of the dappled gray in the other, stared at the beaming Hodja, but could think of not a word to say.

"Wasn't it fun to fool that pompous old Judge?" chuckled the Hodja. "I'm going right back to court to tell him it was all a joke - that things are not always what the evidence makes them seem."

Siraj-ed-Din Bey revived quickly, to say, "Ride my horse back.'

"Oh, no. My donkey's lameness is surely gone by now, and Fatima has probably mended my coat."

Back to Jeremy Schiff's personal homepage

Back to Jeremy Schiff's Hodja homepage

Back to "Once the Hodja" mainpage