Back to Jeremy Schiff's personal homepage

Back to Jeremy Schiff's Hodja homepage

Back to "Once the Hodja" mainpage

HIGH on a mountain trail, Nasr-ed-Din Hodja pulled his donkey to a sudden stop. The ring of an axe, the sound of a man's voice, and the tinkling of donkey bells told him there was companionship in this lonely spot. And the Hodja did like people who would talk and listen. He turned his donkey into a tiny footpath that led toward the sounds.

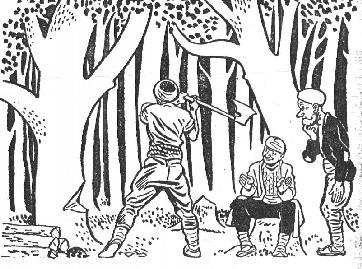

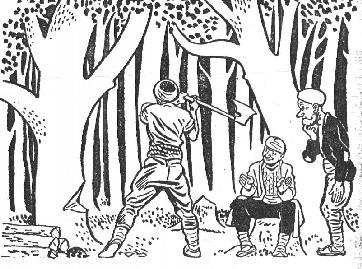

Soon he came upon a group of six donkeys grazing on some cleared land. On all sides were piles of wood cut into stove lengths. Near by was a muscular man swinging an axe. The woodcutter stepped quickly back as a pine tree swayed, moaned, and toppled to the ground. On a stump in the cool shade sat a neatly dressed man who clapped and applauded as the tree fell.

"Bravo, my strong woodcutter!" cheered this second man who was not much more than half the size of the woodcutter. "That was a fine, big tree we cut. That will keep Siraj-ed-Din Bey warm many a winter day. Haidi bakalum! On to the next tree!"

Without looking at his comfortable companion, the woodcutter walked around an oak tree to decide where it should fall, took a firm grip on his axe handle, and started swinging just above the tree's roots.

Each time the woodcutter's axe bit into the tree, the little man on the stump would grunt. The Hodja sat on his donkey, watching this strange performance - the strong man swingmg the axe without a sound passing his lips while the sitting man kept up a steady flow of grunts, groans, and cheers. It was too much for the Hodja's curiosity.

"Why do you make all the noise while the other man does all the work?" he asked the little man.

"Oh, I am helping him," chirruped the man. "He has agreed to cut thirty donkey loads of wood for Siraj-ed-Din Bey. Think what a job that would be for one man. I took, pity on him and went into partnership with him. He swings the axe while I grunt and cheer to keep up his courage."

The Hodja watched the woodcutter who was saying nothing, but making the chips fly. "I think," mused the Hodja, "it is the woodcutter's strong arms that give him courage."

The Hodja looked at the sun. It was growing late and he was not finding the two men very lively company. The Hodja gave the low throaty "Ughr-r-r-r," which started the donkey picking its careful way down the mountain trail toward home.

It was a fortnight later that the Hodja came upon the two men of the mountaintop again. He was loitering about the court, just in case the judge might need his advice about anything. It was amazing how often the Hodja's agile wit could pull the Judge's solemn wisdom out of a tangle. The two men of the mountaintop were disputing before the Judge. Their hands moved as fast as their tongues.

"I earned every ghurush of it myself," the big woodcutter was saying. "I did every stroke of the cutting of thirty donkey loads of wood for Siraj-ed-Din Bey. I loaded the wood onto the donkeys. I drove them to Siraj-ed-Din Bey's house, unloaded every stick of the wood alone, and went back to the mountain for more loads."

"He forgets!" the dapper little man of the stump interrupted. "He forgets how I cheered him at his work. I had a grunt for every swing of his axe, and a cheer for every falling tree. I earned a goodly portion of the money which Siraj-ed-Din Bey made the mistake of paying entirely to the woodcutter."

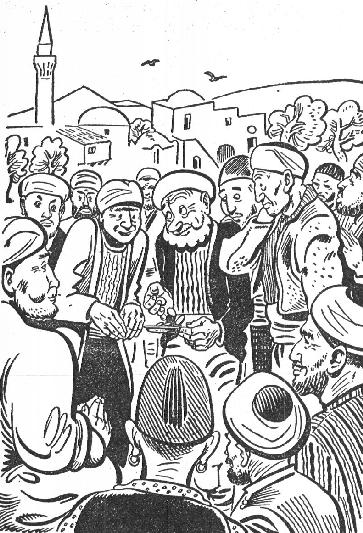

The Judge looked helpless. He had never met just such a case before. There was nothing in his law books about this kind of argument. He was relieved to see the familiar figure of Nasr-ed-Din Hodja elbowing its way through the crowd.

"I turn this case over to my able assistant, Nasr-ed-Din Hodja Effendi," said the Judge, sighing and leaning back, his troubles over. "Repeat your stories to the Hodja."

Both talking at once, the woodcutter and his self-appointed helper told their stories. The Hodja listened, nodding wisely, till both men had talked themselves silent. Then the Hodja beckoned a court attendant. "Bring me a money tray."

The tray was brought. The crowd pressed nearer to see what was going to happen.

"Give me the money, good woodcutter, the money Siraj-ed-Din Bey paid you for the thirty donkey loads of wood."

"But it is my money," pleaded the wood-cutter. "I sweated and toiled for every ghurush of it while this man just sat in the shade and made strange sounds."

"The money, please," repeated the Hodja, holding out his hand for the bag. Reluctantly, the woodcutter passed over the money bag while the little man of the stump drew nearer, his eyes greedily aglitter.

One by one, the Hodja took the coins from the bag and rang them out on the money tray, talking to the man who was claiming a share.

"Do you hear that? Do you like the sound? Isn't that a cheery ring?"

The little man nodded, drawing so close that his nose almost touched the ringing coins. His thumb and forefinger were rubbing together as they itched for the feel of the money.

The last ghurush had left the bag and had made its cheerful ring on the money tray. The big woodcutter writhed to see his hard-earned wages in danger. The little helper smirked to see so much money so near.

"You heard it all?" the Hodja asked the little man.

He nodded hungrily.

"Every ghurush of it?" asked the Hodja.

The little man continued to nod.

"Then you have had your wages." The Hodja began to sweep the money back into the bag. "The sound of the money is proper pay for the sound of working."

The Hodja handed the full money bag to the smiling woodcutter, saying, "And the money is proper pay for the work."

Back to Jeremy Schiff's personal homepage

Back to Jeremy Schiff's Hodja homepage

Back to "Once the Hodja" mainpage